Posted at 15:37h

by cUr@Ayal

66.5cm H x 66.5cm W x 5cm D

2022

Framed in Tasmanian Oak Frame with shou sugi ban finish

'Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.' - Walter Benjamin The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936

As the pandemic unfolded, our world view inadvertently shifted from the physical to the virtual. Our loved ones and colleagues were rendered to the maximum degree of pixel density our devices could handle; we became our front-cameras. The tradition of illusion in art shifted into our palms and we were now the illusion; every online image a masterpiece of trompe l’oeil (deceives the eye).

Of course, well before the pandemic, we willingly became devoted subjects of surveillance capitalism, embracing a marked escalation in technological addiction framed by a backdrop of environmental and economic catastrophe. The subsequent governmentally and socially enforced separation only served to underscore our late-capitalist mentalities: we are alone, but technology can save us. The onset of the pandemic, it seems, was our final, complete baptismal immersion into hyperreality (in case there were any specks of reality still lingering).

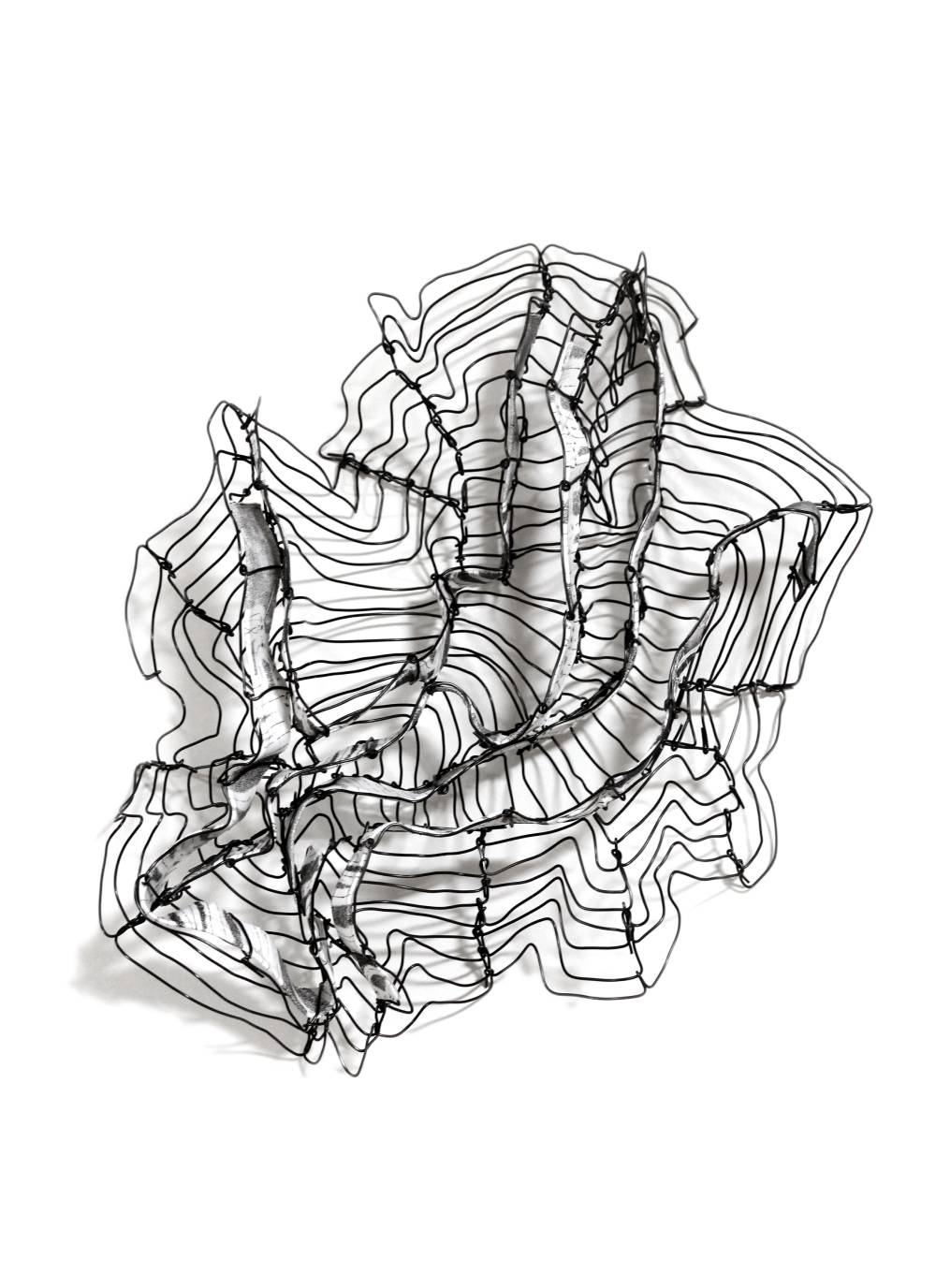

‘Virtual gaze’ has been created with these ideas in mind. The screen is the muse: both its contents and its surface. The works are formal studies into material properties of what comprises a painting or sculpture (for example paint, canvas or stretcher bars) underscoring them as physical objects and therefore exploring their verisimilitude, their reality versus virtuality. They are not images to scroll past, they are paintings. The sparseness of the works disrupt a traditional reading of art - and digital images - where subtly of texture and materiality become vehicles for meaning. Narrative can be interpreted through material, through perception and light, through the sharing of a unique space and time between human and work.

The French painter Charles Lapicque said that the creative act should offer as much surprise as life itself, so for this show works venture well beyond earlier works. Silk obscures and enhances, offering a tech-esque shimmer and obfuscation. Heavily worked metal sits alongside natural linen beside raw rock, an orgy of cavelike primitivism and sophisticated mechanically-produced synthetic material. The imperfect stitch and the few visible marks become focal points and exist almost as accidents: their existence linger as human question marks, as ontological smudges.

Artworks are sometimes arranged as a screen may be, constructed from arranged pixels. The composition for the work, ‘Situating our dreams’, was taken from a composition algorithm generator commissioned and made by a coder in Ukraine. ‘A poem to the future’ was created by a robot vacuum affixed with a paintbrush set free on the canvas. Metal works evoke the industrial nature of the screen, but at the same time contradict this perfection through their organic, vulnerable makeup.

Ironically the JPGs of ‘Virtual gaze’ will become the end product in the lifecycle of the works and will be the way the works will be largely viewed and remembered, reproduced any number of times. The philosopher Walter Benjamin said that technology directly impacts sense and perception, two factors which ultimately affect “humanity’s entire mode of existence”. In a world where we are the product, where we are endlessly reproduced in the hyperreal, you might wonder what Benjamin would say about humanity’s current mode of existence.

Signed on back.